Progress against global hunger has stalled. Why?

A look at what present trends tell us about the future of food security.

Last time, I mentioned that one of the goals of this publication is to try to understand what our global food system will look like in the coming decades. Today I want to begin digging into a prerequisite to that: what is happening with world hunger right now, and where present trends suggest we're headed.

So: why has progress against malnutrition stalled over the course of the past decade?

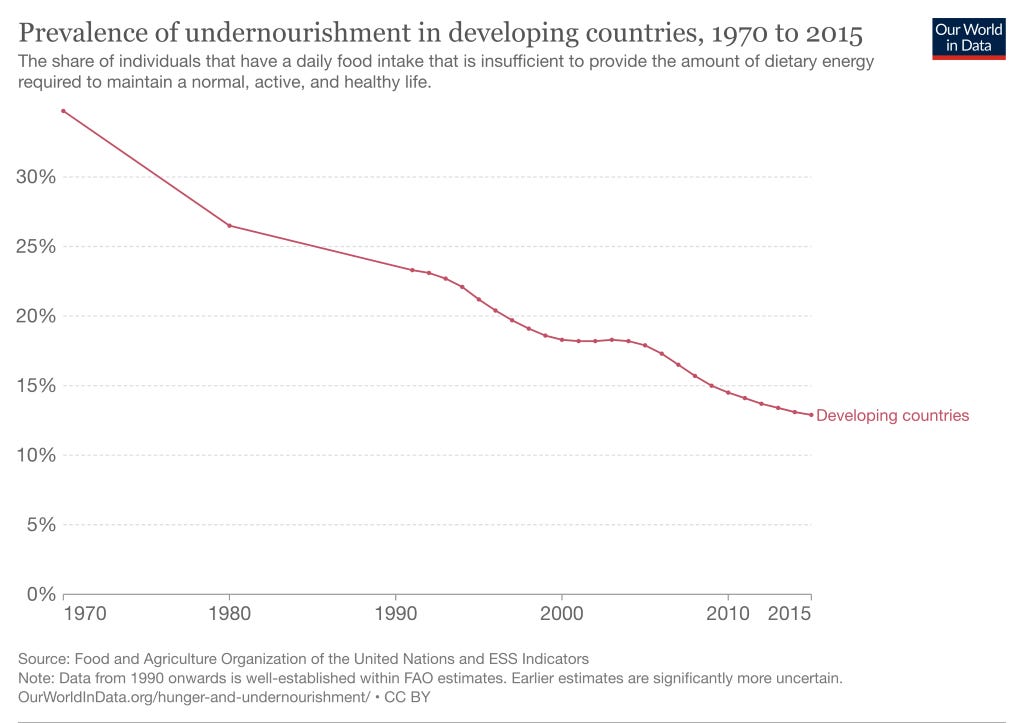

Before tackling that question, it's important to recognize just how much long-term improvement there has been on this front. The chart below from Our World in Data shows a substantial decline in undernourishment in developing countries over the past few decades, from more than 30% in 1970 to around 13% in 2015:

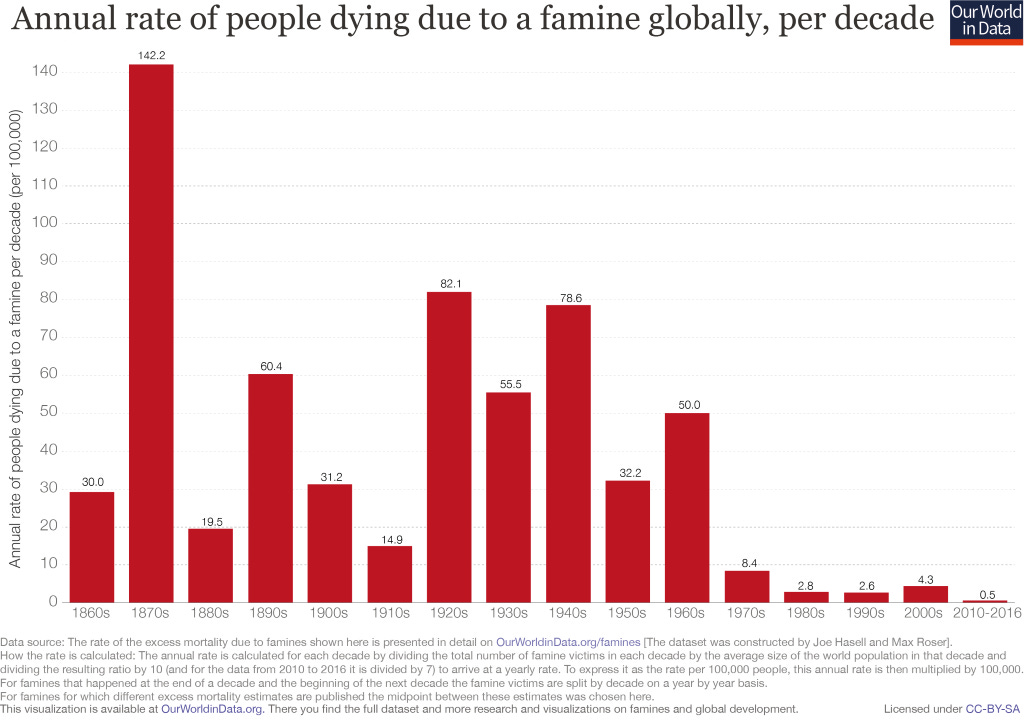

Look back a century and a half or so, and in some ways the difference is even more stark:

It's sometimes implied that these trendlines extend backwards indefinitely; that the situation in the mid-1800s accurately represents all of human history up to that point. I think that's an overly broad assumption. That's a topic for another day, though, and for now the important point is that during the modern era, the trend has been toward fewer people malnourished and dying in famines.

I don’t have a strong understanding of the specific mechanisms that drove this progress. But real improvement arguably began only in the 1970s (think about what the above chart would look like if you call the huge 1870s spike an outlier and remove it). It coincides with the colonized world winning its freedom, global economic growth, and big gains in China in particular.

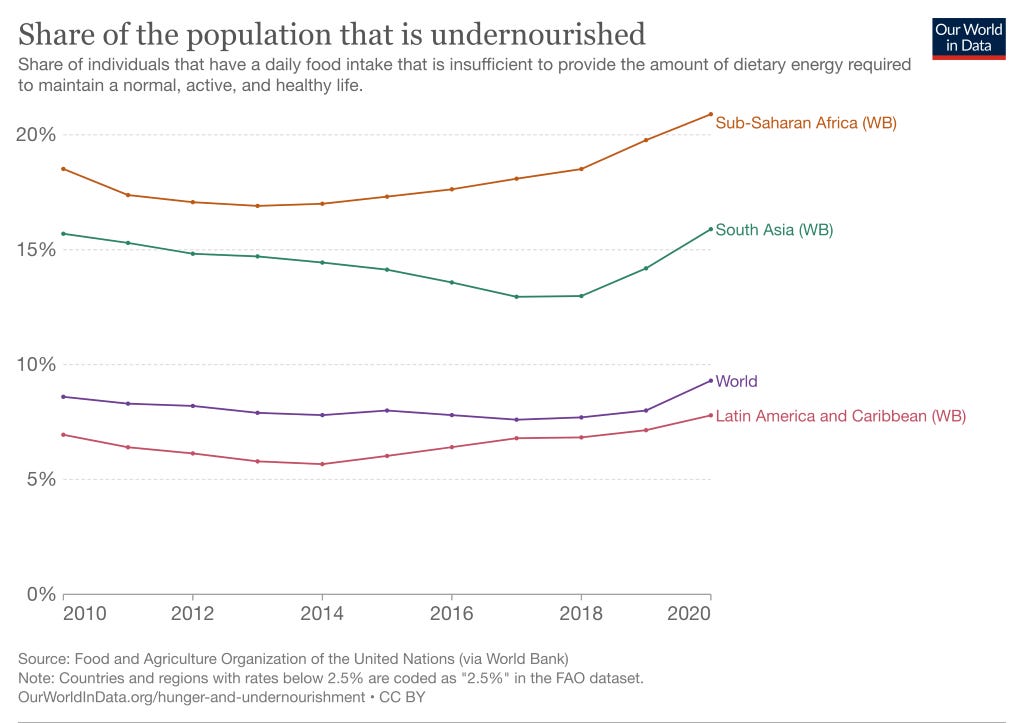

Now let's take a look at the past decade, during which the picture is quite different:

We see the continuation of the steady long-term gains from preceding decades until about 2013. Around then, hunger more or less flatlines until the end of the decade, when undernourishment begins to increase. The obvious explanation for the reversal in recent years is the Covid-19 pandemic, which scrambled supply chains, worsened poverty, and increased food prices. These weren't the only disruptions to food systems, though. In the international development world, a common explanation for the challenges of the pandemic era has been the "three Cs": climate, conflict, and Covid. In addition to the shock of the pandemic, extreme weather has had major impacts on crops, and armed conflict increased by 50% over the past decade or so.

One could argue that the predictable Covid-related spike is less troubling than the less-explicable plateau that began around 2013. That is to say, it's tragic but not altogether surprising that hunger increased during a major global crisis. But why did progress stop and even begin to reverse during quote-unquote "normal" times?

The United Nations puts out an assessment of global food security trends every year, and the report from 2019 is an interesting look at what was happening before the onset of the pandemic. "After decades of steady decline," the report said, "the trend in world hunger – as measured by the prevalence of undernourishment – reverted in 2015, remaining virtually unchanged in the [following three years] at a level slightly below 11 percent."

Because of global population growth, this meant that the absolute numbers of people dealing with malnutrition were modestly increasing. The report estimated that more than 2 billion people were facing moderate food insecurity or worse, classified as not having "regular access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food." One in seven newborn babies suffered from low birthweight, with a trendline flat since 2012. (Childhood stunting, however, was an exception and continued to decline.)

The 2019 report identified three factors that led to the breakdown of progress on undernourishment. Two are already familiar to us: conflict and climate. The third was weak recovery from the global economic crisis of 2008. Of 77 countries with an increase in undernourishment prior to 2019, 65 of them had seen a worsening of economic conditions in preceding years.

As I mentioned above, the economy was the primary vector for COVID-19's impacts on hunger. Undernourishment increased in 2020 not because of the disease itself, but because food production and trade were disrupted by the virus and by measures to contain it. If we group the pandemic and the economy together, we're looking at three core factors responsible for increasing or decreasing hunger: conflict, the climate, and the economy. If these continue to be the three main variables that drive undernourishment, what can we infer about where we're headed?

The economy: Most of the world is now recovering economically from the pandemic. And while there will certainly be more shocks, I assume that aggregate economic growth will remain the norm for the foreseeable future. The question is whether that growth will benefit people who are currently struggling to access adequate food. But it seems plausible to expect that economic trends will continue to be broadly consistent with those that existed while hunger was declining from the 1970s onward.

Climate: Here, on the other hand, there's reason to expect a worsening of conditions. Each additional increment of warming brings with it more extreme heat, storms, droughts, floods and pests that our food systems must cope with. And while the world has made some strides on climate policy in recent years, we're still on track for truly scary levels of warming.

Conflict: I don't really know how one would project whether war is likely to become more or less common in the future. (But if you do, I'm all ears.) There are those who say that climate change is a driver of armed conflict, but that point is contested, and I'm not equipped to provide any sort of conclusive take on it here.

How do we parse the net impact of these factors, with one trending positive, one negative, and one unknown? It seems like that brings us back to a core question of our time—will economic growth and technological progress advance faster than climate damages, and will the benefits of that growth and progress be equitably shared? No predictions from me there. When we’re looking back decades from now, I could imagine the present stagnation appearing either as a fleeting bump on the road to zero hunger, or an inflection point that marked the beginning of bigger problems.